Introduction to Molecular Modelling¶

This section describes a brief concept of molecular modelling to anyone who is new to the subject, including pre-university students.

Computer modelling

Computer modelling is a general term to describe an activity that uses computer software to carry out computation processes, to study the behaviour of a model that simulates a reality, and perhaps to address certain scientific problems.

For centuries, there have been two approaches to obtain solutions to a scientific problem: theoretical and experimental methods.

Theoretical approaches conceptualise a problem, usually in terms of solving some mathematics. Theories offer fundamental insights, leading to possible solutions. However, this sort of approach does not readily show whether a solution is right or wrong, since it is normally a ‘thought’ experiment.

On the other hand, theoretical approaches would often need to be confirmed and tested by carrying out actual experiments, which can relate closely to the real scenario. Even then, experiments often provide directly observed results but not the underlying concepts, causes and mechanisms leading to such experimental observations.

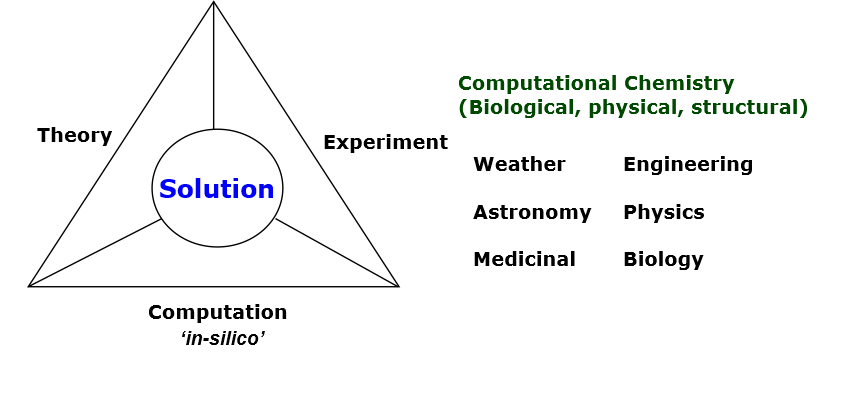

Since the advent of computers, a third approach has emerged to provide solutions to a scientific problem: namely, computational modelling, as shown in the diagram below.

Computational modelling is a complimentary technique that bridges the gaps and effectively covers the inadequacies of the traditional methods.

It is often called ‘in-silico’, implying an investigation, or ‘virtual experiment’ that is conducted on computer silicon chips. This is usually achieved by developing sets of instructions, computer programs, to carry out computation on theoretical concepts that are often difficult or impossible to solve mathematically (by directly solving equations) but are complex enough to simulate experimental conditions.

Computational Chemistry

Nowadays, most modern research in almost every area of scientific discipline involves computer simulations and modelling.

In computational chemistry, we use modelling techniques to investigate the behaviour of atoms and molecules, to explain phenomena that are not accessible by experimental means. Quite often, calculations are also compared against experimental results. As such, computer models can then provide insights to the underlying structures and mechanisms at atomic or molecular scales, to explain materials’ properties and functions.

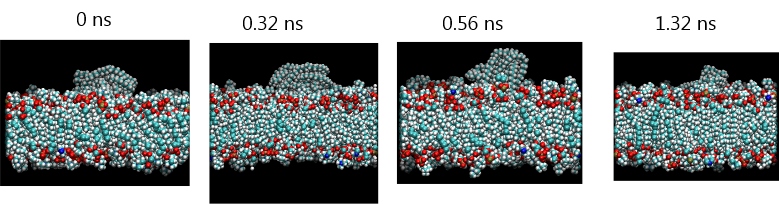

The diagram below shows a series of snapshots produced from molecular simulations showing how a plastic nanoparticle is ingested into a cell membrane. This is an interesting study of the environmental impact at the nanoscale of how industrial production of nanoparticles, or potential environmental degradation of industrial materials into nanoscale particles, may have an impact on animal health.

Note that these images show detailed molecular structures over a length scale of only several nanometres and an extremely fast timescale of less than a nanosecond. Such studies are difficult to carry out experimentally.

In summary molecular modelling can:

- Support theoretical predictions.

- Explain experimental observations.

- Avoid the use of actual equipment or chemicals.

- Precisely set and control experimental (virtual) conditions.

Molecular modelling techniques

There are a number of techniques available to carry out calculations, such as molecular dynamics (MD), Monte Carlo (MC) and ab-initio quantum mechanical methods. Each of these methods uses a different theoretical basis to model and investigate different aspects of atoms and their system behaviour.

If larger numbers of atoms or molecules are involved, coarse-graining approaches can be used to gather together multiple atoms into larger particles or beads and work out how they behave. These can be used with the above techniques or with mesoscale modelling methods to speed up calculations. Some finer atomic detail is lost as a result, but larger systems than those available at atom-based scales can be explored over longer times.

Go to Knowledge Center for more details about simulation techniques.

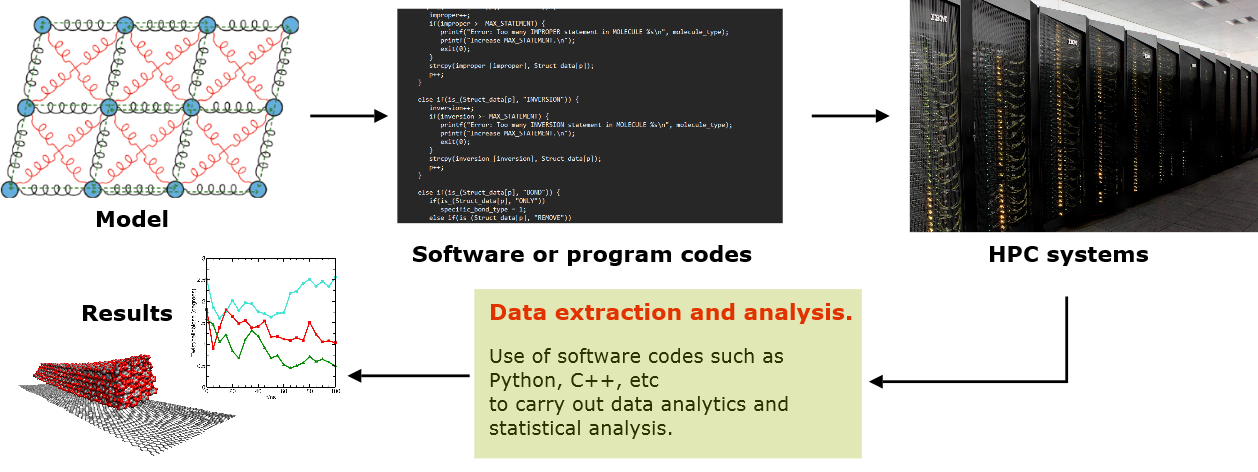

In any case, the theoretical framework would need to be programmed into computer codes. Commonly used languages for computer codes are C, C++ and Fortran. These codes are often compiled (converted from human-readable source code into machine language) and rigorously optimised to maximise computational efficiency, especially with the use of parallel computing algorithms. This means calculations can be distributed over several computer processor cores, each of which can independently carry out part of a single calculation or a set of calculations simultaneously.

These program codes are usually compiled and executed on high performance computers (HPC). These are large computer systems which can handle many different calculations for different users simultaneously: each calculation can use a different number of processor cores. However, modern personal PC desktops and even laptops can also be used, which now commonly have multi-core architectures. Even on the most powerful HPCs, simulations of large system models can span over several weeks and produce many (tens or hundreds of) gigabytes of data at a time.

Quite often, other utility program codes are also developed separately for the purposes of processing and analysing data before results are obtained and presented. These can be written in the same languages as the simulation codes or use interpreted languages such as Python.