Dissipative Particle Dynamics (DPD)¶

Summary¶

Dissipative Particle Dynamics (DPD) is a mesoscale modelling method with many similarities to molecular dynamics, i.e. calculating and integrating forces over a discrete time step to evolve the positions and velocities of particles. DPD features a special pairwise thermostat to control the system temperature while maintaining momentum conservation to ensure correct hydrodynamics. A broad definition of a DPD particle (or ‘bead’) at length scales larger than those for atoms allows the use of soft interaction potentials, allowing longer times to be achieved with fewer time steps than ordinarily available for molecular dynamics (MD). This makes DPD an appealing method to model biomolecular and other biological systems at larger scales than are usually available with atomistic and coarse-grained MD.

Background¶

DPD was originally conceived as an off-lattice form of gas automata [Hoogerbrugge1992] to describe complex fluid flows at larger length scales than those available with molecular dynamics. This algorithm introduced dissipative and random forces between pairs of particles:

which control the particles’ kinetic energy while ensuring local and system momenta are conserved. In the above equations, \(\gamma\) and \(\sigma\) are the dissipative and random force parameters, \(w^{D}\) and \(w^{R}\) are functions of distance for dissipative and random forces respectively, \(\mathbf{r}_{ij} = \mathbf{r}_{j} - \mathbf{r}_{i}\) is the vector between particles \(i\) and \(j\), \({\widehat{\mathbf{r}}}_{ij} = \frac{\mathbf{r}_{ij}}{r_{ij}}\) is the unit vector between the same particles, \(\mathbf{v}_{ij} = \mathbf{v}_{j} - \mathbf{v}_{i}\) is the relative velocity between the two particles, \(\zeta_{ij}\) is a Gaussian random number with zero mean value and unity variance, and \(\Delta t\) is the simulation timestep.

Español and Warren [Español1995] later made the connection between the dissipative and random forces to allow them to act as a Galilean-invariant thermostat. They used the Fokker-Planck equation for fluctuation-dissipation to find the following required conditions for the dissipative and random forces to ensure any equilibrium structure is not affected:

where \(k_B\) is the Boltzmann constant and \(T\) is the required system temperature. With these conditions, the dissipative and random forces make up the DPD thermostat, which can be seen as essentially a pairwise form of the Langevin thermostat. Any flow field applied to a DPD system will thus be treated correctly and the correct hydrodynamics may be observed.

There are no restrictions on how particles otherwise interact in a DPD simulation: indeed, we could use the DPD thermostat for atomistic or coarse-grained MD simulations. That said, if we want to model at the mesoscale, the particles should ideally be larger and softer - compared with those used for atomistic MD - to allow larger timesteps to be used. One very common form of conservative interaction between DPD particles (or ‘beads’) is that proposed by Groot and Warren [Groot1997], which takes the form of a pairwise force that is linear with distance:

where \(r_c\) is an interaction cutoff distance and \(A_{ij}\) is a conservative force parameter. This results in a quadratic potential \(U_{ij} = \frac{1}{2} A_{ij} r_c \left(1 - \frac{r_{ij}}{r_c} \right)^2\) (for \(r_{ij} < r_c\)) and also, for systems with a single particle species, a quadratic equation of state:

where \(\alpha \approx 0.101 r_c^4\) and \(\rho\) is the overall particle density with units of \(r_c^{-3}\). The above equation of state applies when the particle density is greater than 2, and while it is not especially realistic - a cubic equation of state would be better - it is still possible to use it by considering the compressibility of fluids. Its derivative with respect to density at constant temperature provides the reciprocal of isothermal compressibility and this result can then be rearranged to find \(A_{ij}\) for the interactions between beads of a particular species.

There are several methods available to obtain \(A_{ij}\) values between bead pairs of different species. The simplest was devised by Groot and Warren, who made a connection between DPD conservative force parameters and Flory-Huggins solution theory, which specifies \(\chi\) as a measure of free energy of mixing and indicates degree of hydrophobicity. Assuming that like-like interactions - those between pairs of beads of the same species - are the same for all species (\(A_{ij}^{\text{AA}} = A_{ij}^{\text{BB}}\)), the following proportionality applies for a given bead density:

This allows us to find values of \(A_{ij}^{\text{AB}}\) if we happen to know \(\chi^{\text{AB}}\), which can be experimentally determined or estimated from atomistic MD simulations. Other parameterisation strategies exist that make use of infinite dilution activity coefficients [Vishnyakov2013] and water/octanol partition coefficients [Anderson2017].

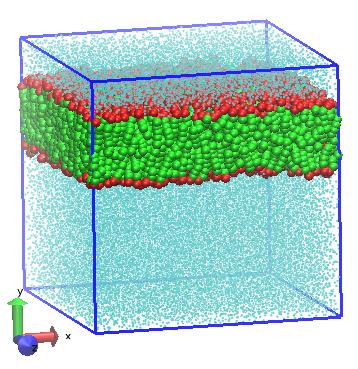

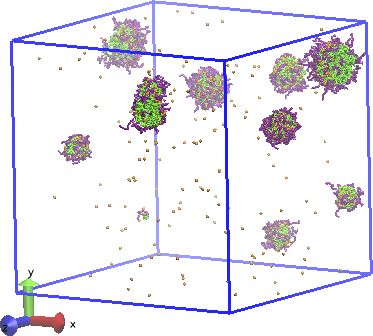

In spite of the simplicity of this interaction, it has been shown to provide enough detail for many complex systems, particularly when used in conjunction with bonded interactions (harmonic springs etc.) between beads to represent amphiphilic molecules with hydrophobic (water-hating) and hydrophilic (water-loving) parts. The softness of the potential makes it possible to attain equilibrium structures in a relatively short time thanks to the use of larger timesteps. As such, it can readily model systems of scientific interest - e.g. vesicles, bilayers, proteins - at length and time scales close to those used in engineering applications.

DPD simulation of bilayer formed from amphiphilic lipid molecules in water [Shillcock2002].

DPD simulation of anti-cancer drug (camptothecin) loading into copolymer vesicles for medical delivery [Luo2012].

Further extensions to the basic Groot-Warren ‘DPD’ interaction have included density-dependent (many-body DPD) potentials to give more realistic equations of state, electrostatic interactions with short-range charge smearing [1] etc. There have additionally been developments to improve the pairwise thermostat, including smarter force integration and alternative pairwise thermostats that can boost fluid viscosity, and it is also possible to couple barostats to the DPD or other pairwise thermostats for constant pressure ensembles.

Footnotes

| [1] | Smearing of charges is generally required for DPD simulations due to the softness of conservative interactions, which may not be sufficiently repulsive to prevent opposite-sign charges from collapsing on top of each other. |

References

| [Hoogerbrugge1992] | PJ Hoogerbrugge and JMVA Koelman, Simulating microscopic hydrodynamic phenomena with dissipative particle dynamics, EPL, 19, p. 155-160, 1992, doi: 10.1209/0295-5075/19/3/001. |

| [Español1995] | P Español and P Warren, Statistical mechanics of dissipative particle dynamics, EPL, 30, p. 191-196, 1995, doi: 10.1209/0295-5075/30/4/001. |

| [Groot1997] | RD Groot and PB Warren, Dissipative particle dynamics: Bridging the gap between atomistic and mesoscopic simulation, Journal of Chemical Physics, 107, p. 4423–4435, 1997, doi: 10.1063/1.474784. |

| [Vishnyakov2013] | A Vishnyakov, M-T Lee and AV Neimark, Prediction of the critical micelle concentration of nonionic surfactants by dissipative particle dynamics simulations, Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, 4, p. 797-802, 2013, doi: 10.1021/jz400066k. |

| [Anderson2017] | RL Anderson, DJ Bray, AS Ferrante, MG Noro, IP Stott and PB Warren, Dissipative particle dynamics: systematic parametrization using water-octanol partition coefficients, Journal of Chemical Physics, 147, 094503, 2017. doi: 10.1063/1.4992111. |

| [Luo2012] | Z Luo and J Jiang, pH-sensitive drug loading/releasing in amphiphilic copolymer PAE–PEG: Integrating molecular dynamics and dissipative particle dynamics simulations, Journal of Controlled Release, 162, p. 185-193, 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.06.027. |